Inertia

| Classical mechanics | ||||||||||

History of classical mechanics · Timeline of classical mechanics

|

||||||||||

Inertia is the resistance of any physical object to a change in its state of motion or rest. It is represented numerically by an object's mass. The principle of inertia is one of the fundamental principles of classical physics which are used to describe the motion of matter and how it is affected by applied forces. Inertia comes from the Latin word, "iners", meaning idle, or lazy. Sir Isaac Newton defined inertia in Definition 3 of his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which states:[1]

The vis insita, or innate force of matter is a power of resisting, by which every body, as much as in it lies, endeavors to preserve in its present state, whether it be of rest, or of moving uniformly forward in a straight line.

In common usage, however, people may also use the term "inertia" to refer to an object's "amount of resistance to change in velocity" (which is quantified by its mass), or sometimes to its momentum, depending on the context (e.g. "this object has a lot of inertia"). The term "inertia" is more properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his First Law of Motion. This law, expressed simply, says that an object that is not subject to any net external force moves at a constant velocity. In even simpler terms, inertia means that an object will always continue moving at its current speed and in its current direction until some force causes its speed or direction to change. This would include an object that is not in motion (velocity = zero), which will remain at rest until some force causes it to move.

On the surface of the Earth the nature of inertia is often masked by the effects of friction, which generally tends to decrease the speed of moving objects (often even to the point of rest), and by the acceleration due to gravity. The effects of these two forces misled classical theorists such as Aristotle, who believed that objects would move only as long as force was being applied to them.[2]

Contents |

History and development of the concept

Early understanding of motion

Prior to the Renaissance in the 15th century, the generally accepted theory of motion in Western philosophy was that proposed by Aristotle (around 335 BC to 322 BC), which stated that in the absence of an external motive power, all objects (on earth) would naturally come to rest in a state of no movement, and that moving objects only continue to move so long as there is a power inducing them to do so. Aristotle explained the continued motion of projectiles, which are separated from their projector, by the action of the surrounding medium which continues to move the projectile in some way.[3] As a consequence, Aristotle concluded that such violent motion in a void was impossible for there would be nothing there to keep the body in motion against the resistance of its own gravity.[4] Then in a statement regarded by Newton as expressing his Principia's first law of motion, Aristotle continued by asserting that a body in (non-violent) motion in a void would continue moving forever if externally unimpeded:

- No one could say why a thing once set in motion should stop anywhere; for why should it stop here rather than here? So that a thing will either be at rest or must be moved ad infinitum, unless something more powerful gets in its way.[5]

Despite its remarkable success and general acceptance, Aristotle's concept of motion was disputed on several occasions by notable philosophers over the nearly 2 millennia of its reign. For example, Lucretius (following, presumably, Epicurus) clearly stated that the 'default state' of matter was motion, not stasis.[6] In the 6th century, John Philoponus criticized Aristotle's view, noting the inconsistency between Aristotle's discussion of projectiles, where the medium keeps projectiles going, and his discussion of the void, where the medium would hinder a body's motion. Philoponus proposed that motion was not maintained by the action of the surrounding medium but by some property implanted in the object when it was set in motion. Although this was not the modern concept of inertia, for there was still the need for a power to keep a body in motion, it proved a fundamental step in that direction.[7][8] This view was strongly opposed by Averroes and many scholastic philosophers who supported Aristotle. However this view did not go unchallenged in the Islamic world, where Philoponus did have several supporters who further developed his ideas.

Chinese theories

Mozi (Chinese: 墨子; pinyin: Mòzǐ; ca. 470 BCE–ca. 390 BCE), a philosopher who lived in China during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (early Warring States Period), composed or collected his thought in the book Mozi, which contains the following sentence: "The cessation of motion is due to the opposing force ... If there is no opposing force ... the motion will never stop." According to Joseph Needham, this a precursor to Newton's first law of motion.[9]

Theory of impetus

In the 14th century, Jean Buridan rejected the notion that a motion-generating property, which he named impetus, dissipated spontaneously. Buridan's position was that a moving object would be arrested by the resistance of the air and the weight of the body which would oppose its impetus.[10] Buridan also maintained that impetus increased with speed; thus, his initial idea of impetus was similar in many ways to the modern concept of momentum. Despite the obvious similarities to more modern ideas of inertia, Buridan saw his theory as only a modification to Aristotle's basic philosophy, maintaining many other peripatetic views, including the belief that there was still a fundamental difference between an object in motion and an object at rest. Buridan also maintained that impetus could be not only linear, but also circular in nature, causing objects (such as celestial bodies) to move in a circle.

Buridan's thought was followed up by his pupil Albert of Saxony (1316–1390) and the Oxford Calculators, who performed various experiments that further undermined the classical, Aristotelian view. Their work in turn was elaborated by Nicole Oresme who pioneered the practice of demonstrating laws of motion in the form of graphs.

Shortly before Galileo's theory of inertia, Giambattista Benedetti modified the growing theory of impetus to involve linear motion alone:

"…[Any] portion of corporeal matter which moves by itself when an impetus has been impressed on it by any external motive force has a natural tendency to move on a rectilinear, not a curved, path."[11]

Benedetti cites the motion of a rock in a sling as an example of the inherent linear motion of objects, forced into circular motion.

Classical inertia

The law of inertia states that it is the tendency of an object to resist a change in motion. According to Newton's words, an object will stay at rest and or stay in motion unless acted on by a net external force, whether it results from gravity, friction, contact, or some other source. The Aristotelian division of motion into mundane and celestial became increasingly problematic in the face of the conclusions of Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, who argued that the earth (and everything on it) was in fact never "at rest", but was actually in constant motion around the sun.[12] Galileo, in his further development of the Copernican model, recognized these problems with the then-accepted nature of motion and, at least partially as a result, included a restatement of Aristotle's description of motion in a void as a basic physical principle:

A body moving on a level surface will continue in the same direction at a constant speed unless disturbed.

It is also worth noting that Galileo later went on to conclude that based on this initial premise of inertia, it is impossible to tell the difference between a moving object and a stationary one without some outside reference to compare it against.[13] This observation ultimately came to be the basis for Einstein to develop the theory of Special Relativity.

Galileo's concept of inertia would later come to be refined and codified by Isaac Newton as the first of his Laws of Motion (first published in Newton's work, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in 1687):

Unless acted upon by a net unbalanced force, an object will maintain a constant velocity.

Note that "velocity" in this context is defined as a vector, thus Newton's "constant velocity" implies both constant speed and constant direction (and also includes the case of zero speed, or no motion). Since initial publication, Newton's Laws of Motion (and by extension this first law) have come to form the basis for the almost universally accepted branch of physics now termed classical mechanics.

The actual term "inertia" was first introduced by Johannes Kepler in his Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae (published in three parts from 1618–1621); however, the meaning of Kepler's term (which he derived from the Latin word for "idleness" or "laziness") was not quite the same as its modern interpretation. Kepler defined inertia only in terms of a resistance to movement, once again based on the presumption that rest was a natural state which did not need explanation. It was not until the later work of Galileo and Newton unified rest and motion in one principle that the term "inertia" could be applied to these concepts as it is today.

Nevertheless, despite defining the concept so elegantly in his laws of motion, even Newton did not actually use the term "inertia" to refer to his First Law. In fact, Newton originally viewed the phenomenon he described in his First Law of Motion as being caused by "innate forces" inherent in matter, which resisted any acceleration. Given this perspective, and borrowing from Kepler, Newton actually attributed the term "inertia" to mean "the innate force possessed by an object which resists changes in motion"; thus Newton defined "inertia" to mean the cause of the phenomenon, rather than the phenomenon itself. However, Newton's original ideas of "innate resistive force" were ultimately problematic for a variety of reasons, and thus most physicists no longer think in these terms. As no alternate mechanism has been readily accepted, and it is now generally accepted that there may not be one which we can know, the term "inertia" has come to mean simply the phenomenon itself, rather than any inherent mechanism. Thus, ultimately, "inertia" in modern classical physics has come to be a name for the same phenomenon described by Newton's First Law of Motion, and the two concepts are now basically equivalent.

Relativity

Albert Einstein's theory of Special Relativity, as proposed in his 1905 paper, "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," was built on the understanding of inertia and inertial reference frames developed by Galileo and Newton. While this revolutionary theory did significantly change the meaning of many Newtonian concepts such as mass, energy, and distance, Einstein's concept of inertia remained unchanged from Newton's original meaning (in fact the entire theory was based on Newton's definition of inertia). However, this resulted in a limitation inherent in Special Relativity that the principle of relativity could only apply to reference frames that were inertial in nature (meaning when no acceleration was present). In an attempt to address this limitation, Einstein proceeded to develop his theory of General Relativity ("The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity," 1916), which ultimately provided a unified theory for both inertial and noninertial (accelerated) reference frames. However, in order to accomplish this, in General Relativity Einstein found it necessary to redefine several fundamental aspects of the universe (such as gravity) in terms of a new concept of "curvature" of spacetime, instead of the more traditional system of forces understood by Newton.

As a result of this redefinition, Einstein also redefined the concept of "inertia" in terms of geodesic deviation instead, with some subtle but significant additional implications. The result of this is that according to General Relativity, when dealing with very large scales, the traditional Newtonian idea of "inertia" does not actually apply, and cannot necessarily be relied upon. Luckily, for sufficiently small regions of spacetime, the Special Theory can still be used, in which inertia still means the same (and works the same) as in the classical model.

Another profound, perhaps the most well-known, conclusion of the theory of Special Relativity was that energy and mass are not separate things, but are, in fact, interchangeable. This new relationship, however, also carried with it new implications for the concept of inertia. The logical conclusion of Special Relativity was that if mass exhibits the principle of inertia, then inertia must also apply to energy as well. This theory, and subsequent experiments confirming some of its conclusions, have also served to radically expand the definition of inertia in some contexts to apply to a much wider context including energy as well as matter.

Interpretations

According to Isaac Asimov

According to Isaac Asimov in "Understanding Physics": "This tendency for motion (or for rest) to maintain itself steadily unless made to do otherwise by some interfering force can be viewed as a kind of 'laziness', a kind of unwillingness to make a change." And indeed, Newton's laws of motion, as Isaac Asimov goes on to explain, "represent assumptions and definitions and are not subject to proof. In particular, the notion of 'inertia' is as much an assumption as Aristotle's notion of 'natural place'.... To be sure, the new relativistic view of the universe advanced by Einstein makes it plain that in some respects Newton's laws of motion are only approximations.... At ordinary velocities and distance, however, the approximations are extremely good."

Mass and inertia

Physics and mathematics appear to be less inclined to use the original concept of inertia as "a tendency to maintain momentum" and instead favor the mathematically useful definition of inertia as the measure of a body's resistance to changes in momentum or simply a body's inertial mass.

This was clear in the beginning of the 20th century, when the theory of relativity was not yet created. Mass, m, denoted something like amount of substance or quantity of matter. And at the same time mass was the quantitative measure of inertia of a body.

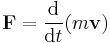

The mass of a body determines the momentum  of the body at given velocity

of the body at given velocity  ; it is a proportionality factor in the formula:

; it is a proportionality factor in the formula:

The factor m is referred to as inertial mass.

But mass as related to 'inertia' of a body can be defined also by the formula:

Here, F is force, m is mass, and a is acceleration.

By this formula, the greater its mass, the less a body accelerates under given force. Masses  defined by the formula (1) and (2) are equal because the formula (2) is a consequence of the formula (1) if mass does not depend on time and speed. Thus, "mass is the quantitative or numerical measure of body’s inertia, that is of its resistance to being accelerated".

defined by the formula (1) and (2) are equal because the formula (2) is a consequence of the formula (1) if mass does not depend on time and speed. Thus, "mass is the quantitative or numerical measure of body’s inertia, that is of its resistance to being accelerated".

This meaning of a body's inertia therefore is altered from the original meaning as "a tendency to maintain momentum" to a description of the measure of how difficult it is to change the momentum of a body.

Inertial mass

The only difference there appears to be between inertial mass and gravitational mass is the method used to determine them.

Gravitational mass is measured by comparing the force of gravity of an unknown mass to the force of gravity of a known mass. This is typically done with some sort of balance scale. The beauty of this method is that no matter where, or on what planet you are, the masses will always balance out because the gravitational acceleration on each object will be the same. This does break down near supermassive objects such as black holes and neutron stars due to the steep gradient of the gravitational field around such objects.

Inertial mass is found by applying a known force to an unknown mass, measuring the acceleration, and applying Newton's Second Law, m = F/a. This gives an accurate value for mass, limited only by the accuracy of the measurements. When astronauts need to be weighed in the weightlessness of free fall, they actually find their inertial mass in a special chair.

The interesting thing is that, physically, no difference has been found between gravitational and inertial mass. Many experiments have been performed to check the values and the experiments always agree to within the margin of error for the experiment. Einstein used the fact that gravitational and inertial mass were equal to begin his Theory of General Relativity in which he postulated that gravitational mass was the same as inertial mass, and that the acceleration of gravity is a result of a 'valley' or slope in the space-time continuum that masses 'fell down' much as pennies spiral around a hole in the common donation toy at a chain store. Dennis Sciama later showed that the reaction force produced by the combined gravity of all matter in the universe upon an accelerating object is mathematically equal to the object's inertia [1], but this would only be a workable physical explanation if by some mechanism the gravitational effects operated instantaneously.

Since Einstein used inertial mass to describe Special Relativity, inertial mass is closely related to relativistic mass and is therefore different from rest mass.

Inertial frames

In a location such as a steadily moving railway carriage, a dropped ball (as seen by an observer in the carriage) would behave as it would if it were dropped in a stationary carriage. The ball would simply descend vertically. It is possible to ignore the motion of the carriage by defining it as an inertial frame. In a moving but non-accelerating frame, the ball behaves normally because the train and its contents continue to move at a constant velocity. Before being dropped, the ball was traveling with the train at the same speed, and the ball's inertia ensured that it continued to move in the same speed and direction as the train, even while dropping. Note that, here, it is inertia which ensured that, not its mass.

In an inertial frame all the observers in uniform (non-accelerating) motion will observe the same laws of physics. However observers in another inertial frame can make a simple, and intuitively obvious, transformation (the Galilean transformation), to convert their observations. Thus, an observer from outside the moving train could deduce that the dropped ball within the carriage fell vertically downwards.

However, in frames which are experiencing acceleration (non-inertial frames), objects appear to be affected by fictitious forces. For example, if the railway carriage were accelerating, the ball would not fall vertically within the carriage but would appear to an observer to be deflected because the carriage and the ball would not be traveling at the same speed while the ball was falling. Other examples of fictitious forces occur in rotating frames such as the earth. For example, a missile at the North Pole could be aimed directly at a location and fired southwards. An observer would see it apparently deflected away from its target by a force (the Coriolis force) but in reality the southerly target has moved because earth has rotated while the missile is in flight. Because the earth is rotating, a useful inertial frame of reference is defined by the stars, which only move imperceptibly during most observations.The law of inertia is also known as Isaac Newton's first law of motion.

In summary, the principle of inertia is intimately linked with the principles of conservation of energy and conservation of momentum.

Source of Inertia

There is no single accepted theory that explains the source of Inertia. Various efforts by notable physicists such as Ernst Mach (see Mach's principle), Albert Einstein, D Sciama, and Bernard Haisch have all run into significant criticisms from more recent theorists. For recent treatments of the issue see C. Johan Masreliez (2006)[14] and Vesselin Petkov (2009)[15].

Rotational inertia

Another form of inertia is rotational inertia (→ moment of inertia), which refers to the fact that a rotating rigid body maintains its state of uniform rotational motion. Its angular momentum is unchanged, unless an external torque is applied; this is also called conservation of angular momentum. Rotational inertia depends on the object remaining structurally intact as a rigid body, and also has hidden practical consequences. For example, a gyroscope uses the property that it resists any change in the axis of rotation.

See also

- General relativity

- Inertial guidance system

- Kinetic Energy

- List of moments of inertia

- Mach's principle

- Newton's laws of motion

- Newtonian physics

- Special relativity

- Steiner theorem

Notes

- ↑ Isaac Newton, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy translated into English by Andrew Motte, First American Edition, New York, 1846, page 72.

- ↑ Pages 2 to 4, Section 1.1, "Skating", Chapter 1, "Things that Move", Louis Bloomfield, Professor of Physics at the University of Virginia, How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary, John Wiley & Sons (2007), hardcover, 720 pages, ISBN 978-0-471-74817-5

- ↑ Aristotle, Physics, 8.10, 267a1-21; Aristotle, Physics, trans. by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye.

- ↑ Aristotle, Physics, 4.8, 214b29-215a24.

- ↑ Aristotle, Physics, 4.8, 215a19-22.

- ↑ Lucretius, On the Nature of Things (London: Penguin, 1988), pp, 60-65

- ↑ Richard Sorabji, Matter, Space, and Motion: Theories in Antiquity and their Sequel, (London: Duckworth, 1988), pp. 227-8; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: John Philoponus.

- ↑ David J. Darling(2006), Gravity's arc: the story of gravity, from Aristotle to Einstein and beyond

- ↑ Joseph Needham; Science and Civilisation in China

- ↑ Jean Buridan: Quaestiones on Aristotle's Physics (quoted at http://brahms.phy.vanderbilt.edu/a203/impetus_theory.html)

- ↑ Giovanni Benedetti, selection from Speculationum, in Stillman Drake and I. E. Drabkin, Mechanics in Sixteenth Century Italy University of Wisconsin Press, 1969, p. 156.

- ↑ Nicholas Copernicus: The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, 1543

- ↑ Galileo: Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, 1631 (Wikipedia Article)

- ↑ Masreliez, C.J., Motion, Inertia and Special Relativity – a Novel Perspective, Physica Scripta, (dec 2006)

- ↑ "Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime", Chapter 9, by Vesselin Petkov, 2nd ed. (2009)

References

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001a), "Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's Motion in Context", Science in Context (Cambridge University Press) 14 (1-2): 145–163

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001b), "Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science", Osiris, 2nd Series 16 (Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions): 49–64 & 66–71

External links

Books and papers

- Butterfield, H (1957) The Origins of Modern Science ISBN 0-7135-0160-X

- Clement, J (1982) "Students' preconceptions in introductory mechanics", American Journal of Physics vol 50, pp 66–71

- Crombie, A C (1959) Medieval and Early Modern Science, vol 2

- McCloskey, M (1983) "Intuitive physics", Scientific American, April, pp 114–123

- McCloskey, M & Carmazza, A (1980) "Curvilinear motion in the absence of external forces: naïve beliefs about the motion of objects", Science vol 210, pp1139–1141

|

|||||